News

Mining Procurement: A Strategic Shift from Bias to Best Practice

November 7, 2025

“This document presents a compelling argument that this subjective approach is not a minor inefficiency but a severe, quantifiable risk to financial performance, operational safety, and organisational integrity.”

- Context: The document’s core thesis on the danger of traditional, subjective procurement.

The mining industry operates in a world of extreme pressure, where capital projects carry immense stakes and operational missteps can have catastrophic consequences. In this environment, the procurement function has traditionally been managed through intuition, entrenched personal relationships, and “gut-feel.”

This document presents a compelling argument that this subjective approach is not a minor inefficiency but a severe, quantifiable risk to financial performance, operational safety, and organisational integrity. It further outlines a comprehensive, high-reliability framework designed to replace this dysfunction with a transparent, data-driven system that serves as a bedrock for sustainable value and risk mitigation.

Conversations take place on a mine (fictional) in Australia:

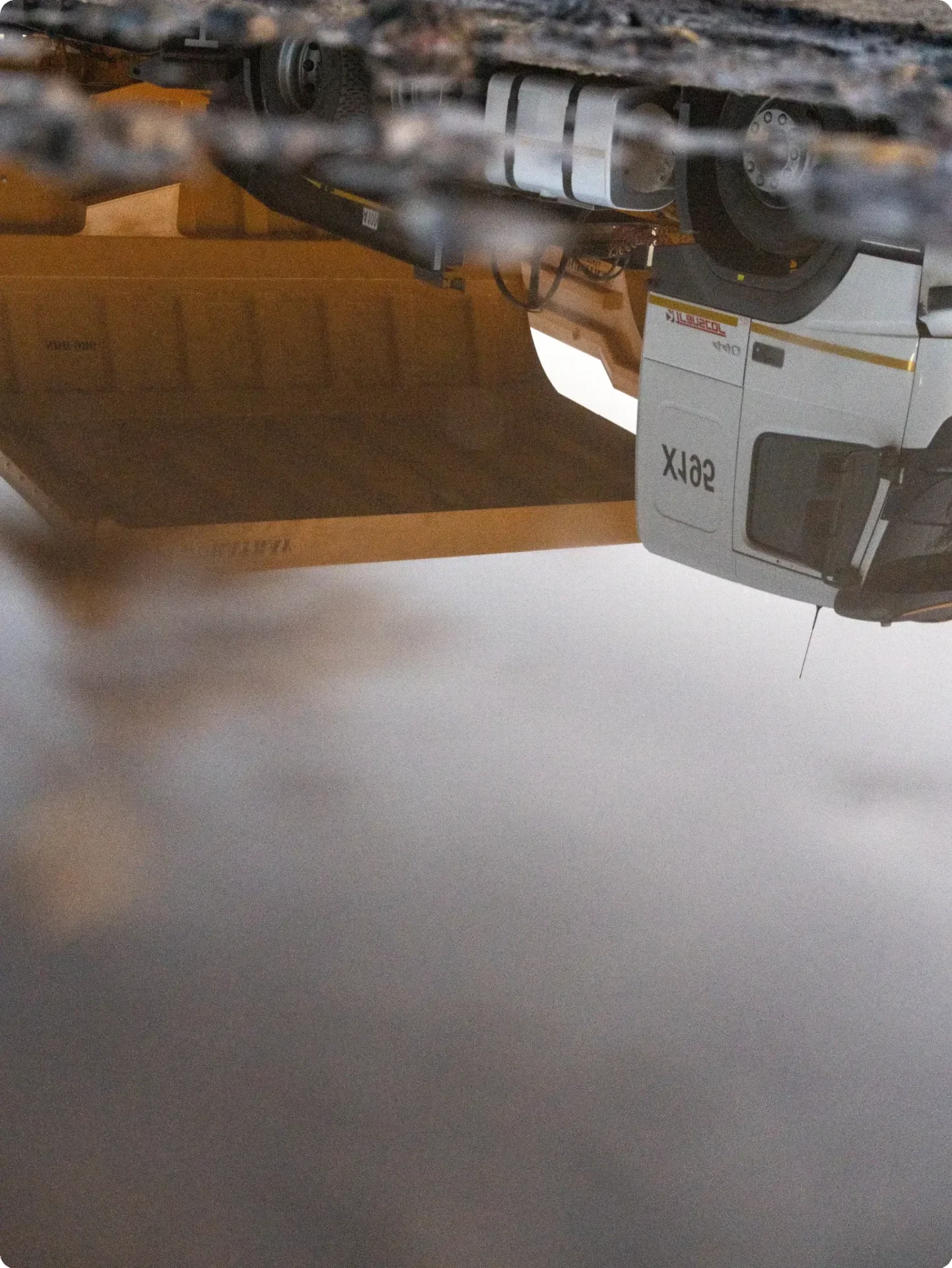

Scene: Yandicoogina North

The conversations are taking place at Yandicoogina North, a sprawling, open-cut iron ore mine in the heart of Western Australia’s Pilbara region.

The landscape is a vast, ancient canvas of deep red earth and spinifex grass, carved into massive terraces by decades of blasting and digging. The sky is a relentless, metallic blue, and the heat, even by 9 AM, is a physical weight, baking the site in 40°C+ temperatures.

A constant, low-frequency roar from the haul truck fleet – each vehicle the size of a two-storey house – fills the air, overlaid with the high-pitched screech of the primary crusher and the rattle of kilometres-long conveyor systems. Fine red dust hangs in the air, coating every surface and finding its way into everything.

The “action” of the conversations doesn’t happen out in the pit, but in the “village” – a cluster of air-conditioned, pre-fabricated buildings (or “dongas”) that serve as the site offices.

Bill’s office is functional but cluttered. The walls are thin, and through them, he can hear the constant crackle of the two-way radio and the hum of the overworked air-conditioner. On his wall, a large, stained whiteboard is covered in production targets, maintenance schedules, and budget figures. The numbers for the month are circled in red, and the pressure to “make tonnage” is the unspoken context for every decision, every shortcut, and every heated conversation.

The Core Problem: A Self-Reinforcing Triad of Dysfunction

“Flawed procurement decisions are rarely isolated incidents. They are the symptomatic output of a deeply rooted systemic failure, composed of three interconnected elements that create a self-sustaining cycle of poor performance.”

Flawed procurement decisions are rarely isolated incidents. They are the symptomatic output of a deeply rooted systemic failure, composed of three interconnected elements that create a self-sustaining cycle of poor performance.

Let’s break down each element, starting with the flawed decision-making process itself.

1. Unchecked Cognitive Biases in Decision-Making

Human psychology, particularly under pressure, often overrides rational analysis. In the high-stakes context of a mine site, this manifests in predictable and costly cognitive biases.

The most financially damaging of these is Myopia Bias: a fixation on the low initial purchase price while ignoring the long-term Total Cost of Ownership (TCO). A manager incentivised on capital expenditure savings may choose a cheaper component, blindly accepting its future exorbitant maintenance and downtime costs.

This bias is not just theoretical; it creates a toxic internal dynamic known as the “Bad Advice” Cycle, which is enabled by the second part of the triad: a Corrosive Blame Culture.

Conversation Scenario: The “Bad Advice” Cycle

This conversation illustrates how Myopia Bias and a Blame Culture force a direct report to give “bad advice.”

Setting: Bill’s (Manager) office. They’re looking at two quotes for new gearbox components.

Bill: “Righto, Sarah. Got the quotes from ‘Rhino Gear’ and ‘Apex Industrial’. The Apex gear is 30% cheaper. That’s a bloody good save for this quarter. I’m keen on that.”

Sarah: (Hesitantly) “Yeah, look, Boss… I’ve run the numbers. The Rhino parts are good for 20,000 hours. This Apex rubbish? 8,000, if we’re lucky. We’ll be swapping ’em out three times as often. When you factor in the downtime, the blokes on the tools, and the lost production… it’ll cost us double in the long run. Dead set.”

Bill: (Leans back, frowning) “Mate, ‘long run’ doesn’t help my CAPEX this month. I need to show a win now, not next year. Are you telling me your crew can’t make ’em work? Don’t forget the headache you caused last time you brought up all that TCO stuff in the budget meeting.”

Sarah: (Recognises the warning. Bill isn’t asking, he’s telling. Arguing will just put her offside, and she’ll cop the blame for the budget.)

Sarah: (Sighs, changing her tone) “…Yeah, nah, you’re right, boss. A 30% saving is huge. She’ll be right. We’ll just… we’ll just have to wear the extra maintenance. No worries.”

Bill: “Too easy. Knew you’d see it my way. Good on ya. We’ll book the saving, you just handle the fallout. Beauty.”

A TCO analysis reveals that a ‘biased’ low-price decision for a haul truck can cost a company over $7.5 million in higher operating costs over five years, dwarfing the initial ‘savings.’”

- Context: The quantifiable impact of Myopia Bias (Section 1).

The quantifiable impact of this “saving” is devastating. A TCO analysis reveals that a “biased” low-price decision for a haul truck can cost a company over $7.5 million in higher operating costs over five years, dwarfing the initial “savings.”

This dysfunctional culture also encourages other biases, such as Confirmation Bias, where decision-makers subconsciously seek out and overweight information that confirms their pre-existing beliefs.

Conversation Scenario: Confirmation Bias & The “Preferred Supplier”

This shows how “entrenched relationships” and Confirmation Bias corrupt the process before TCO is even considered.

Setting: Bill is on the phone in his office, talking to “Mick,” a long-time supplier he plays golf with.

Bill: “Mick, mate, how are ya? …Hey, listen, I’ve got this tender out for new conveyor rollers. Your mob’s in for it, but the bean-counters are giving me grief about your price. They’ve got this other quote from ‘Apex’ that’s 20% cheaper.”

Mick (on phone): “Ah, mate, ‘Apex’? You’re kidding! Their stuff’s rubbish. Absolute rubbish… You get what you pay for, Bill. You know that.”

Bill: (Nodding) “Yeah, that’s what I thought. I knew their stuff was dodgy. Knew it. My gut told me. Thanks, Mick, appreciate the heads-up. I’ll sort it out my end. Cheers.”

(Bill hangs up. Sarah walks in.)

Sarah: “Gaffer, I’ve finished the scorecard analysis for the roller tender. On paper, Apex wins. Their TCO is better, their defect rate is certified, and…”

Bill: (Holding his hand up) “Stop right there. I’ve just been on the blower. I’m not using Apex. Their gear is rubbish… My gut says Mick’s gear is better, and it’s just been confirmed. End of story.”

“The manager who operates on ‘gut-feel’ is often flying blind because their own leadership style has destroyed the data streams needed to make an informed decision.”

These biases culminate in Overconfidence Bias, where experienced managers overestimate their own “gut-feel” and dismiss data-driven models. When this bias inevitably leads to failure, the Blame Culture kicks in to find a scapegoat, leading to a total collapse of data integrity.

Conversation Scenario: Manager & Report (The Aftermath: Blame & Data Collapse)

This conversation illustrates Overconfidence Bias and the resulting Data Integrity Collapse.

Setting: Bill’s office, the day after the gearbox from the first scenario failed catastrophically.

Bill: “Two. Bloody. Days. Sarah! Two days of production down the gurgler ’cause that gearbox failed. You told me your crew could handle it!”

Sarah: “And we did! We’ve already swapped it out twice, just like the TCO model reckoned we would… The components are rubbish, Bill. The data proves it.”

Bill: (Slams his hand on the desk) “I don’t give a stuff about your ‘models’! I’ve been running this pit for 20 years. My gut told me this was a simple swap-out. Your data is just noise! The real problem is your crew clearly isn’t fitting ’em right. It’s shoddy work.”

Sarah: (Stunned) “Bull. We followed the procedure to the letter.”

Bill: “Your data’s wrong. My experience tells me it’s a fitting error. Now, I have to file a report. I want you to ‘clean up’ that data. All those ‘near-misses’? They just muddy the water… Just get it done.”

Bill’s order to “clean up the data” perfectly illustrates the catastrophic breakdown in information integrity. Studies of safety climate data reveal an average 25% underreporting rate for all incidents, with up to 45% of serious incidents “flying under the radar,” intentionally hidden from view. The manager who operates on “gut-feel” is often flying blind because their own leadership style has destroyed the data streams needed to make an informed decision.

2. The Obsolete Adversarial Supplier Model

This internal dysfunction of bias and blame inevitably spills over into external relationships, creating the third element of the triad: an outdated, transactional procurement mindset.

“The manager’s ‘ego response’ leads to the rejection of valuable ‘free intelligence.’ A supplier attempting to provide consulting on operational inefficiencies is treated as a personal attack.”

Conversation Scenario: Manager & Supplier (Rejecting “Free Intelligence”)

This conversation illustrates the Adversarial Supplier Model and the “Ego Response” to valuable feedback.

Setting: On the mine floor. The conveyor is down. David (the supplier who lost the bid) is on-site for a different job.

David: “Bill, mate. Rough trot with the conveyor, ay? …I clocked something on that new gearbox you fitted… the telemetry’s all over the shop. Looks like the bearing is already carking it… Look, I can get my tech to run a full diag if you want? Give you the data…”

Bill: (Face hardens) “Hang on, are you trying to flog me something, David? ‘Cause it sounds a lot like you’re just here to say ‘I told you so’. I’ve got enough dramas today without a supplier having a sook.”

David: “Nah, mate, dead serious. I’m just offering some data… just offering a bit of free intel, that’s all.”

Bill: “I don’t need ‘free intel’. I need my crew to fix what’s busted. You just stick to your contract, mate, and let me worry about my pit.”

This non-transparent, relationship-driven model doesn’t just block good suppliers; it creates critical security vulnerabilities. In regions like South Africa, it has enabled the rise of a “procurement mafia,” where organised criminal syndicates extort contracts.

Conversation Scenario: The “Security Vulnerability” (The “Procurement Mafia”)

This illustrates how a non-transparent system is vulnerable to extortion.

Setting: Bill’s ute, at a “random” stop-check on the access road. A “Community Liaison Officer” (part of an extortion syndicate) is at his window.

Community Officer: (Smiling) “Morning, Mr Bill… we heard you have a big tender out for transport. For the diesel. It would be a shame if the trucks couldn’t get through, you know? With all the ‘community protests’ lately.”

Bill: (Grips the steering wheel) “What are you saying?”

Community Officer: “I’m saying, there’s a local company, ‘Bantfu Logistics’… If he got the contract, I could guarantee that all your diesel trucks would be… safe. Your system is very… flexible. You make the call based on ‘best-fit’, yes? I’m just telling you who the ‘best-fit’ is for a peaceful operation.”

“A biased, non-transparent system has no defence against this. A transparent, rule-based procurement process (Pillar 1) acts as an essential ‘security shield,’ allowing a manager to say, ‘My hands are tied. It’s all based on the data.’”

Principle: A biased, non-transparent system has no defence against this. A transparent, rule-based procurement process (Pillar 1) acts as an essential “security shield,” allowing a manager to say, “My hands are tied. It’s all based on the data.”

The Remediation Framework: Three Interlocking Pillars for Change

Solving this systemic problem requires a coordinated, multi-dimensional approach. The following three pillars must be implemented in concert to create a self-reinforcing cycle of reliability.

Pillar 1: Structural Solutions & Pillar 3: Leadership Solutions

The first and third pillars work in concert. The goal is to re-engineer the procurement process to be objectively governed (Pillar 1), which requires a new model of leadership (Pillar 3) to champion it.

- Pillar 1: Structural Solutions:

- Mandate Total Cost of Ownership (TCO): The TCO model must be the non-negotiable standard for all significant procurement decisions, systematically countering Myopia Bias.

- Implement Objective Supplier Scorecards: Move beyond subjective “trust” to weighted performance metrics (e.g., On-Time Delivery, Quality, TCO Performance, Safety/Compliance).

- Pillar 3: Leadership Solutions:

- Champion Leader Humility: The ultimate antidote to the “ego response.” A humble leader acknowledges their limitations, appreciates their team’s strengths, and is open to feedback.

- Contextual Decision-Making (Cynefin Framework): This guides leaders to use “gut-feel” only for true Chaotic crises (like a mine collapse), but to use analytical, data-driven processes for Complicated problems like procurement.

When these two pillars are combined, the adversarial relationship transforms into a strategic partnership.

Positive Scenario: The Strategic Partnership

This shows the antidote to the Adversarial Model, built on Objective Scorecards (Pillar 1) and Leader Humility (Pillar 3).

Setting: A formal quarterly review. Jane (an effective manager) is with David (the good supplier).

Jane: “Right, David, let’s pull up the new Supplier Scorecard for Q3. …Okay, On-Time Delivery, 98%. Green. Quality/Defect Rate… 0.2%. Green. Good stuff. But I see our TCO metrics are amber.”

David: “Yeah, I wanted to talk to you about that. We’ve been tracking the performance… the data from your own system, which you share with us, shows they’re wearing 15% faster than in any other mine we service.”

Jane: (Leans forward, concerned) “15%? Why? Is it a bad batch?”

David: “No, our analysis shows it’s the process. The vibration data suggests your operators are running the trucks at 110% load… shredding the components.”

Jane: (Sighs) “Right. That’s not good. It’s probably a shortcut to hit tonnage targets.”

David: “Exactly. So, here’s our ‘free intelligence’: we’ve developed a 10-minute training module for your operators… We can roll it out with your team. No charge.”

“You’re not just selling me parts, you’re selling me performance.” (From the Positive Scenario: The Strategic Partnership)

Jane: “David, that’s brilliant. That’s exactly why we have this partnership. You’re not just selling me parts, you’re selling me performance. Let’s get that implemented by Friday.”

Pillar 2: Cultural Solutions – Fostering Psychological Safety and a Just Culture

That positive external partnership can only exist if the internal culture is healthy. A new system (Pillar 1) is useless if it is fed bad data, and that data relies on Psychological Safety (Pillar 2).

This means actively dismantling the Blame Culture and implementing a “Just Culture.” This is not a “no-blame” culture, but a fair one. It distinguishes between:

- Human Error (consoling & improving systems)

- At-Risk Behaviour (coaching)

- Reckless Conduct (punitive action)

This shift is the prerequisite for building the psychological safety necessary for staff to report errors accurately, breaking the “bad advice’ cycle” and providing the clean data required for the structural solutions to work.

Positive Scenario: The “Just Culture” in Action

This conversation shows the antidote to the Blame Culture. It focuses on the system, not the person.

Setting: Jane’s office. Sarah comes in, looking worried.

Sarah: “Gaffer, I’ve got to report something. One of the new fitters, young Tommo… used the wrong-spec lube oil. Completely wrong. We caught it before it did any damage, but the procedure is right there on the tablet.”

Jane: (Puts her pen down, gives her full attention) “Righto. First up, good catch. Well done to the team for spotting it. Is Tommo alright? He’s probably bricking it.”

Sarah: “Yeah, he’s pretty shaken. I told him to stand by, that I’d sort it.”

Jane: “Good. Now, let’s look at the system. This is Tommo’s first week off his apprenticeship, yeah? Why did he grab the wrong oil? Are the drums marked clearly? Are they stored next to each other? Is the part number in the procedure identical to the drum label…?”

Sarah: “Well… now that you mention it, the store-man has been complaining that the new labels are confusing…”

Jane: “See? That’s the problem. This isn’t a ‘Tommo’ problem, it’s a ‘labelling’ problem. A ‘human error’ is a symptom of a system failure. Let’s get Tommo in here, you, and the store-man. We’re not here to pin the blame, we’re here to fix the bloody labels so it can’t happen again. Good work, Sarah.”

Conclusion and Imperative for Action

The transformation from “cowboy” procurement to a high-reliability function is not merely a procedural change – it is a strategic imperative. The modern mining industry, facing heightened scrutiny and complex risks, can no longer afford the staggering hidden costs of biased decision-making.

“Effective leadership is no longer defined by the quality of one’s intuition alone, but by the wisdom to know when to subordinate it to a robust, transparent, and data-driven framework.”

Effective leadership is no longer defined by the quality of one’s intuition alone, but by the wisdom to know when to subordinate it to a robust, transparent, and data-driven framework.

By implementing this three-pillar approach, mining companies can shield themselves from catastrophic financial losses, operational failures, and external threats, turning their procurement function from a vulnerability into a definitive source of strength and value.